Picto Diary - 21 September 2019 - Ring of Brodgar; Orkney, Part 3

Above: Standing Stones of Stennis. Orkney, Scotland. 21 September 2019

Out and about in Orkney.

TIMDT finds new stones to channel Claire.

The Standing Stones of Stenness is a Neolithic monument five miles northeast of Stromness on the mainland of Orkney, Scotland. This may be the oldest (5500 years old) henge site in the British Isles.

By far the largest and tallest stones we have seen on this trip. — with Margaret Taylor at Standing Stones of Stenness.

Above: Standing Stones of Stennis. Orkney, Scotland. 21 September 2019.

Out and about in Orkney.

Forget Claire.... TIMDT channels Dave!

Thus Spake Zarathustra

Above: The Ring of Brodgar. Orkney, Scotland. 21 September 2019.

The Ring of Brodgar is a Neolithic henge and stone circle in Orkney, Scotland. Most henges do not contain stone circles; Brodgar is a striking exception, ranking with Avebury (and to a lesser extent Stonehenge) among the greatest of such sites.

The ring of stones stands on a small isthmus between the Lochs of Stenness and Harray. These are the northernmost examples of circle henges in Britain. Unlike similar structures such as Avebury, there are no obvious stones inside the circle, but since the interior of the circle has never been excavated by archaeologists, the possibility remains that wooden structures, for example, may have been present.

The site has resisted attempts at scientific dating and the monument's age remains uncertain. It is generally thought to have been erected between 2500 BC and 2000 BC, and was, therefore, the last of the great Neolithic monuments built on the Ness.

The stone circle is 104 metres (341 ft) in diameter, and the third largest in the British Isles. The ring originally comprised up to 60 stones, of which only 27 remained standing at the end of the 20th century. The tallest stones stand at the south and west of the ring, including the so-called "Comet Stone" to the south-east.

The stones are set within a circular ditch up to 9.8 ft deep, 30 ft wide and 1,250 ft in circumference that was carved out of the solid sandstone bedrock by the ancient residents. in this case on the north-west and south-east. The ditch appears to have been created in sections, possibly by workforces from different parts of Orkney. The stones may have been a later addition, maybe erected over a long period of time.

Examination of the immediate environs reveals a concentration of ancient sites, making a significant ritual landscape. Though its exact purpose is not known, the proximity of the Standing Stones of Stenness and its Maeshowe tomb make the Ring of Brodgar a site of major importance. The site is a scheduled ancient monument and has been recognized as part of the "Heart of Neolithic Orkney" World Heritage Site in 1999.

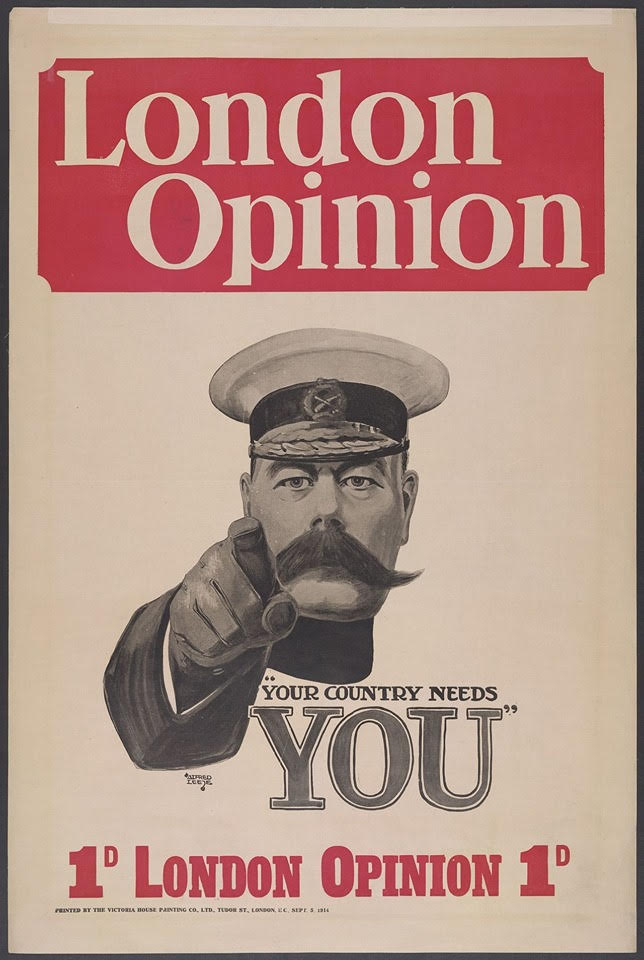

Above: Kitchener Monument. Kitchener Poster. Orkney, Scotland. 21 September 2019.

Out and about in Orkney. .

In 1914, at the start of the First World War, Herbert Kitchener became Secretary of State for War, a Cabinet Minister. One of the few to foresee a long war, lasting for at least three years, and with the authority to act effectively on that perception, he organized the largest volunteer army that Britain had seen, and oversaw a significant expansion of materials production to fight on the Western Front.

Despite having warned of the difficulty of provisioning for a long war, he was blamed for the shortage of shells in the spring of 1915 – one of the events leading to the formation of a coalition government – and stripped of his control over munitions and strategy.

On 5 June 1916, the veille of The Battle of the Somme, Kitchener was making his way to Russia on HMS Hampshire to attend negotiations with Tsar Nicholas II when the ship struck a German mine 1.5 miles (2.4 km) west of the Orkneys, Scotland, and sank. Kitchener was among 737 who died.

The monument, constructed in 1926, is on the North Sea coastline, 1.5 miles from the point of the sinking.

The monument's inscription:

"This tower was raised by the people of Orkney in memory of Field Marshall Earl Kitchener of Khartoum on that corner of his country which he had served so faithfully nearest to the place where he died on duty. He and his staff perished along with the officers and nearly all the men of HMS Hampshire on 5th June, 1916."

This visit to the Orkneys mark's, even if in a small way, another Bishop visit to a WWI theater. I made visits of two weeks each to Gallipoli and Flanders/French WWI battlefields in 2016.

In addition to the Kitchener Monument we visited nearby Scapa Flow today. Each locale brings focus onto the primary sea campaign of WWI.

Germany's aggressive fleet buildup in the years prior to WWI never matched Britain's naval strength, but Germany was closing in and England was getting a bit nervous about it. Germany's August 1914 invasion of Belgium was the putative excuse for Britain to enter WWI, but there is little doubt that UK unease about Germany's naval bellicosity made the decision easier.

To protect Atlantic sea lanes and to thwart a German naval threat, Britain positioned most of it's Grand Fleet at the strategically located, and well protected harbor, Scapa Flow, here in the Orkney Islands.

The German fleet enjoyed safe harbor in Wilhelmshaven. With the Western Front bogged down in seeming stalemate trench warfare, The High Seas Fleet (German) left port for the first time in in the war on 30 May 1916 in the hope's of luring the Grand Fleet (British) into the open.

On 31 May 1916, the High Seas and Grand fleets engaged in the only significant sea battle of WWI, The Battle of Jutland, off the coast of Denmark. In terms of tonnage sunk, the Germans won the battle. However, the British fleet remained formidable and returned down, but not out, to Scapa Flow after the battle.

The German fleet high tailed it back to home port, Wilhelmshaven. Only once during WWI did the High Fleet leave Wilhelmshaven after The Battle of Jutland. And that foray was to intern the German fleet with Britain at nearby Scapa Flow in 1919, pursuant to stipulations of the Armistice negotiations. So, in hindsight, give the Battle of Jutland to the Brits on a TKO. After Jutland despite their losing more tonnage than the Germans at.Jutland, the Brits had neutralized German sea power for the remainder of the war.

Lord Kitchener might have been feeling optimistic as he was sailing into the North Sea just five weeks after the Grand Fleet had stalemated the High Seas Fleet at the Battle of Jutland. But, the nation of Great Britain experienced more than a moment of despair when Kitchener's life, and the lives of 700 crew of the battleship .....were snuffed out by a German mine.

No doubt at least some Germans saw the Battle of Jutland stalemate in a better light after Kitchener's untimely death.

Only a month later, 01 July 1916, would the allies launch the battle of The Somme in France. Unfortunately for Britain and the Entente, yet another reason for augmenting German self confidence.

Addendum:

Odd, when you consider it: 5000 years ago, tribes from all over the world who couldn't even know there were other people on the other side of the world, were all moving 30 to 100 ton cut-out stones to build structures to preserve their dead, usually to join them with their gods in the sky.

KAT,

Dallas, TX

Great info. Thanks Steve.

Brandman,

Ventura, CA