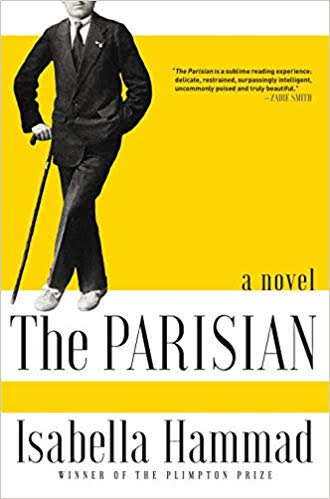

"The Parisian" by Isabella Hammad

Above: "The Parisian" - Isabella Hammad - 551 Pages.

"The Parisian" is set, mainly, in immediate post WWI, Nablus, Palestine. The novel's timeline runs from 1915, when protagonist Midhat, son of a successful Nablus clothing merchant, attends medical school in Montpelier, France, to the mid 1930's when seeming irresolvable violence and tension are rife between Jews and Arabs in the British Mandate of Palestine.

I completed reading this book today.

On a late September afternoon, in 1963, I was seated in a wicker chair at a wicker glass topped table in the student lounge, American University in Cairo (Egypt). Also, at the table, were six newfound student friends. Three of my new friends, like me in their late teens, were Palestinian men. They (the three Palestinians) were all well dressed... long sleeved, collared shirts, shiny dress shoes, pressed dress slacks, yada. They wore gold chains around their necks. Pomade black haired, dark eyed and Mediterranean in complexion, they sported mustaches and goatees. Imagine 3x Omar Sharif. All at the table were smokers, Their speech was in grammatically impeccable, emotive English. Put another way, they spoke, though heavily accented, better English than I did.

I would later appreciate that my new friends' seeming sophistication - it intimidated me at the time - derived from the fact that they came from wealthy families and had been educated in the Middle East's best prep schools. The distinctive, pungent smell of Gauloise cigarette smoke wafted through the air. I was the only non smoker in the group. There was one female in our group, Farida, a Coptic Christian Egyptian girl. She and I would later become an item... a story for another time.

We talked about Palestine.

Only three months previously, I had graduated from Provo High School in what had to be one of the most homogenous school populations anywhere: predominantly white, LDS, imbued with "Leave it to Beaver," naivety and optimism.

We knew we lived in a comforting place. Middle class as we were, we still possessed our own brand of elitism. We were among the earliest of the baby boomers. In post war America, the sky was the limit as to our potential. We were all taught... and we all believed... that if we worked hard enough we could be President of the US. Most of us looked forward to going off to college, to the service, or on LDS missions. After that, we'd marry and have families. We were upbeat about the future. Even better, buttressed by LDS teachings, we knew our happiness would be eternal.

Now, only months later, seated with a group of new international college friends in Egypt (!) I was listening to a discussion about... Palestine. The discussants were noticeably less sanguine about their future than I had been about mine back in Provo.

As I look back, the disjunction of this Cairo scene relative to the "happy valley" life I had left only months earlier, seems more dissonant each time I think about it. It turned out that my experience in Cairo would be a life transformational experience. I didn't know that at the time... but, that, too, is a story to be recounted later.

Back to Palestine. I'll never forget the intensity and passion of the three Palestinian students as they railed about the injustice done to their families by the Jews. "Our homes, our properties, our businesses were stolen from us by the Jews," they exclaimed! "We can go to the West Bank (then administered by Palestinian friendly Jordan), and see our homes, across the Mandelbaum gate into Israel, occupied by a callous Jewish invader."

It was in Cairo, in 1963, where I first learned, from my Palestinian friends, about what would be one of the most difficult, intractable world conflicts that would endure throughout my life time. The Arab/Israeli conflict.

Later, in 1964, I visited the Jordanian sector of Jerusalem, in the West Bank. I saw first hand, what my Palestinian companions were talking about. Still a teenager, I stood at the Mandelbaum Gate, the checkpoint between the Israeli and Jordanian sectors of Jerusalem, just north of the western edge of the Old City along the Green Line.

The Mandelbaum Gate would exist until the 1967 Six-Day War, when victorious Israel would take charge, directly, of the entire West Bank, and, all of Jerusalem. The Mandelbaum Gate had existed from the close of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War at the time of the exit of Britain from its Mandate responsibilities. Pre 1948, properties in Israeli Jerusalem had been owned and occupied by the families of the young students I was hanging out with in Cairo. I could see erstwhile Palestinian properties as I looked across the Mandelbaum gate into Israel.

Then (1963), fifteen years since their families lost their properties, my young student friends in Cairo, most of whom were three or four years old when they had to leave Palestine, still seethed.

Today, the enmity of a new generation of Palestinians, rages as strongly as ever at the putative expropriating of their homeland by the Jews. Somehow, the Brits, who legitimized the Zionist movement, were let off the hook in this plaint.

This book review is not the place to write about the intricacies and injustices or otherwise of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict. There are compelling arguments for both sides. There are also important issues, such as the nature of culture to be discussed and understood. Clearly, the British tipped the scales to facilitate Jewish mass immigration to Palestine... but, again, this is another story for a different time.

"The Parisian" is Isabella Hammad's first novel. Hammad was born of Palestinian heritage in London. She obtained her undergraduate degree in English Language and Literature from Oxford University. In 2012 she was awarded a Kennedy Scholarship to Harvard, and in 2013 she received the Harper Wood Creative Writing Studentship from Cambridge University.

Hammad is winner of The Plimpton Prize. The Plimpton Prize for Fiction is an award of $10K given to a new voice published in the Paris Review. The prize is named for the Review's longtime editor George Plimpton and reflects his commitment to discovering new writers of exceptional merit.

"The Parisian" is set, mainly, in immediate post WWI, Nablus, Palestine. The novel's timeline runs from 1915, when protagonist Midhat, son of a successful Nablus clothing merchant, attends medical school in Montpelier, France, to the mid 1930's when seeming irresolvable violence and tension are rife between Jews and Arabs in the British Mandate of Palestine.

The novel is, essentially, a saga of a Palestinian family's fitfull adaptation to a changing world around them as thousands of new, Jewish immigrants arrive.

Russian pogroms and the rise of Nazi power in Germany provided the impetus for thousands of Jews to immigrate to Palestine. Britain's cooperation with the London based Zionist movement, enabled unparalleled immigration numbers relative to the capacity of the small Arab nation's ability to absorb them...at least without intense cultural friction.

It's one thing to have sympathy for the Jewish people having undergone (and yet to undergo, via the perfidy of Nazi Germany) unconscionable persecution. But, Hammad's novel, and not in a testy or nasty or partisan way, asks us to witness the transformation of Palestine through the lens of the long time resident Palestinians.

To be sure, the Jews occupied Palestine in ancient, Biblical times. And, in the early 20th century, Jewish immigrants legitimately paid their way into Palestine. They didn't seize Palestine by force. Palestinians sold their land and properties to Jewish immigrants for "top dollar."

Jewish immigrants were enterprising. They started farms, they built trading and manufacturing businesses. The process leading to dominant Jewish influence was slow. At first all got along. It was not uncommon in early post WWI Palestine to find a Palestinian and a Jew in business together.

But, as the Jewish population grew, its homogenous culture began to crowd out the Palestinians. What does the local Palestinian manufacturer of cement do when a new cement factory, established by Jews, creates an improved production process, lowers costs, and under prices his long held product monopoly?

Arab, Midhat, " the Parisian," our novel's protagonist, returns, with a patina of European sophistication, in 1919 from four years in France, to greet his father in Cairo, location of an important arm of the family business.

Midhat had experienced a bad ending to a relationship with a French girl in Montpelier. He quit medical school after one year and moved to Paris where he studied political science. He had befriended young Arabs in Paris who formed part of the budding Arab independence movement.

Unbeknownst to Midhat, his stern, traditional father intercepted a letter from his Montpelier lover who, full of apologies and regret, wished to renew her relationship with Midhat. Midhat's father, not showing the letter to his son, immediately moved to arrange Midhat's marriage in the traditional Muslim fashion.

Midhat, torn between his experiences of Westen freedom and his traditional religious and family loyalties, opts to follow his father's dicta. But, the lingering memory of his French relationship, and the notion of a world outside Islam, never disappears from his thoughts. Midhat is not always able to remain sane as the his simultaneous ambivalence about competing worlds rends his soul.

Midhat, having never learned of his French lover's attempt to reconcile, is now surrounded by his own family, a "true catch wife" and three kids, grandmother, cousins, and half brothers/sisters of his father's second wife in Cairo. Midhat renews friendship with his Arab friends from Paris, many of whom become underground, Arab independence activists against the British and oppsing Jewish movements, seeking their own of independence.

As the living climate in Nablus deteriorates... business shuts down... gunfire is heard every night.... Midhat negotiates the conflicting pressures of supporting his family, aligning with Palestinian political opposition to Britain and the Jews, business, and his lingering memories of France.

Hammad's writing is beautiful. It's the kind of writing you want to read out loud, just to enhance the lyrical power and beauty of her phrasing.

At one point, Midhat convalesces in a British hospital... mental breakdown. He reads to pass the time. Here's a snip of Hammad's writing: "He forced his way through the paragraph of Montesquieu. He was shifting heavy sand, trying to uncover something hard beneath. He felt the pieces of his mind like the wheels of a clock running too slow."

The novel is replete with evocative, metaphorical writing such as the above. I like to write... but, I realize what a crappy writer I really am when I am forced to confront the truth that I will never be able to summon up the words...the figures of speech, to compete with Hammad's evocative writing style.

The book is long... saga like. It's written in three parts. Having a recent passion about studying WWI and having lived in France for two and one half years (1965-1968) and the middle east for 18 months (Cairo,1963/1964; Beirut, 1972), I enjoyed every word.

I felt like I knew the novel's characters from personal experience. And, from my experiences with my aggrieved Palestinian friends in 1964 Cairo, in a way, I did.

Hammad's narrative, a historical novel with fictional characters, gave me a lens through which to view a poignant struggle of a people overwhelmed by events beyond their control. I now, having read "The Parisian," better understand the angst and anger of the three Gauloise smoking Palestinians I met at the student union in Cairo.